If you meander around Freeport’s Winslow Park where it juts out into the Harraseeket River, you might see Emily Selinger hoisting heavy bags of oysters from the row of black floats that make up her oyster farm into her white skiff.

While Selinger sells oysters by the piece to farmers market customers in Bath and Portland, she primarily operates Emily’s Oysters as a community-supported fishery (CSF) business, which, like a community-supported agriculture farm, allows customers to buy shares of the future harvest. “It’s an investment,” Selinger says. “I have a fantastic customer base that I know and that knows me. They trust I’ll be there. They like my oysters.”

CSFs are fast-growing, direct sales operations that demonstrated their worth when the pandemic upended global industrial supply chains. When folks couldn’t find cod, clams, or crab in supermarkets, they could often buy an array of fresh seafood directly from fishermen.

Emily’s Oysters is one of hundreds of small, independent seafood businesses across North America comprising the Local Catch Network. Spearheaded by Josh Stoll, who is an assistant professor of marine policy at University of Maine, and several fisheries colleagues from across the country, the network provides resources to help its member businesses launch, grow, and thrive.

Emily’s Oysters is one of hundreds of small, independent seafood businesses across North America comprising the Local Catch Network. Spearheaded by Josh Stoll, who is an assistant professor of marine policy at University of Maine, and several fisheries colleagues from across the country, the network provides resources to help its member businesses launch, grow, and thrive.

The national network rose out of Walking Fish, a project Stoll ran in 2009 with a group of North Carolina fishermen who brought freshly harvested seafood to the faculty and staff of Duke University, plus the surrounding Durham community.

“People were inspired by this model,” Stoll says. “They were interested in rethinking food systems, rethinking fisheries, moving from [a] higher-volume, low-value model to a lower-volume, high-value model. They liked the idea of using seafood as a platform to engage people in this dialogue about conservation, about community, and about sustainability.”

Formally established in 2011, the Local Catch Network runs out of UMaine and comprises over 500 fishermen, small seafood business owners, researchers, and consumers committed to sourcing, selling, and buying locally caught, healthy, low-impact, and economically sustainable seafood. Core values like community-based fisheries and fair pricing bind these network members together.

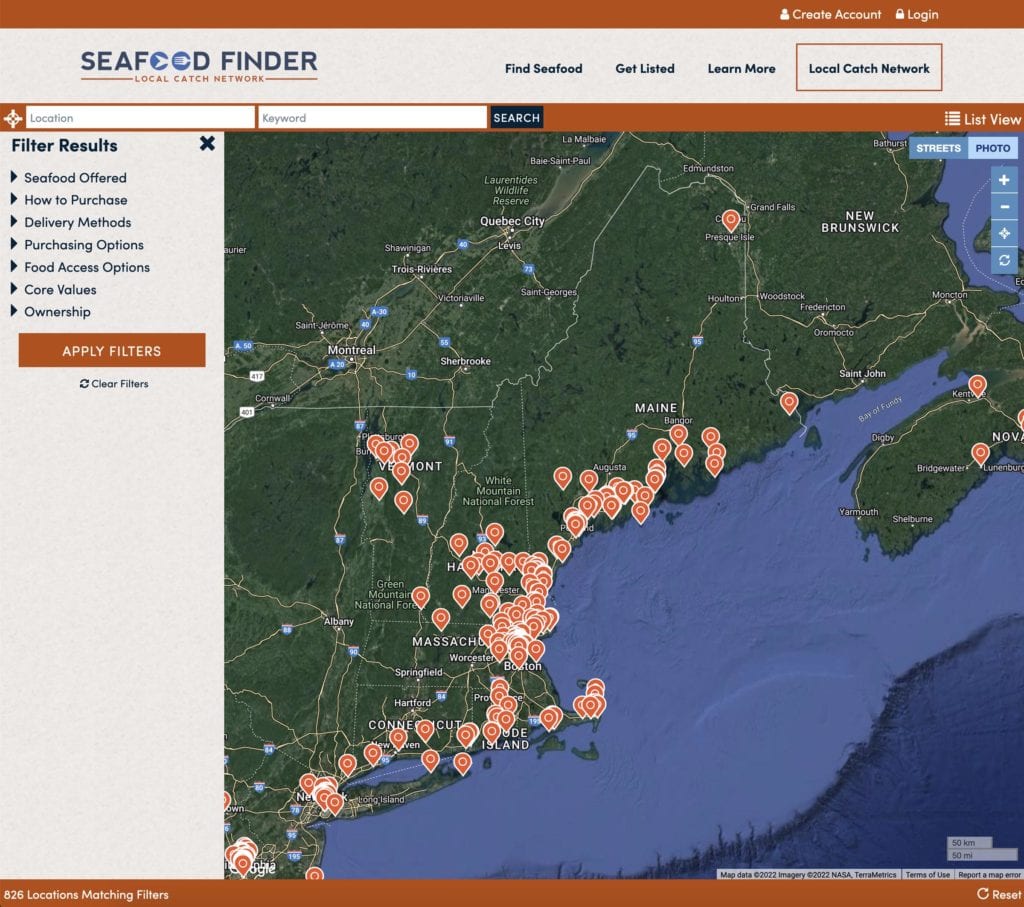

Consumers can find Local Catch Network members near them via the organization’s interactive map (finder.localcatch.org). There are dozens of Maine-based seafood operations on the map, with another 10 pinpointed in southern New Hampshire.

Network members benefit from these direct sales matchups but also from access to grants, training opportunities, and seafood market research. The Local Catch Network recently won a USDA $500,000 grant that supports its new Scale Your Local Catch business accelerator program, a series of classes centered on business-critical topics like direct marketing, accounting, insurance, labor, and taxation.

Tim Sheehan of Gulf of Maine, Inc. participated in the program last winter as he plans to expand his Pembroke-based seafood sales operation that sells scallops, periwinkles, and seaweed to consumers and a variety of marine species to universities and research centers around the world for scientific analyses.

The network has hosted three Local Seafood Summit gatherings since 2012, with a 2022 meetup slated for early October in Girdwood, Alaska. These events enable fishermen and small business owners to share stories, network, and learn new approaches to seafood harvesting, processing, and sales, as well as how to address regulatory and marketing challenges.

The network has hosted three Local Seafood Summit gatherings since 2012, with a 2022 meetup slated for early October in Girdwood, Alaska. These events enable fishermen and small business owners to share stories, network, and learn new approaches to seafood harvesting, processing, and sales, as well as how to address regulatory and marketing challenges.

The Local Catch Network’s focus on community-based fisheries drew Sheehan to the network’s 2016 summit in Norfolk, Virginia. “It’s nice to know there are other people fighting the same battles and looking to do the same kind of work,” says Sheehan. In one working group, Tim and his wife Amy swapped ideas with Alaskan fishermen and fishmongers about packaging techniques and overnight shipping. A connection with a couple from Australia led to Sheehan’s 19-year-old son fishing and processing fish with the couple near Coorong Lagoon for two months.

It is heartening that a Maine-based collaborative geared toward getting people to rethink food systems has such a global reach.