What would you say is Maine’s most quintessential ingredient?

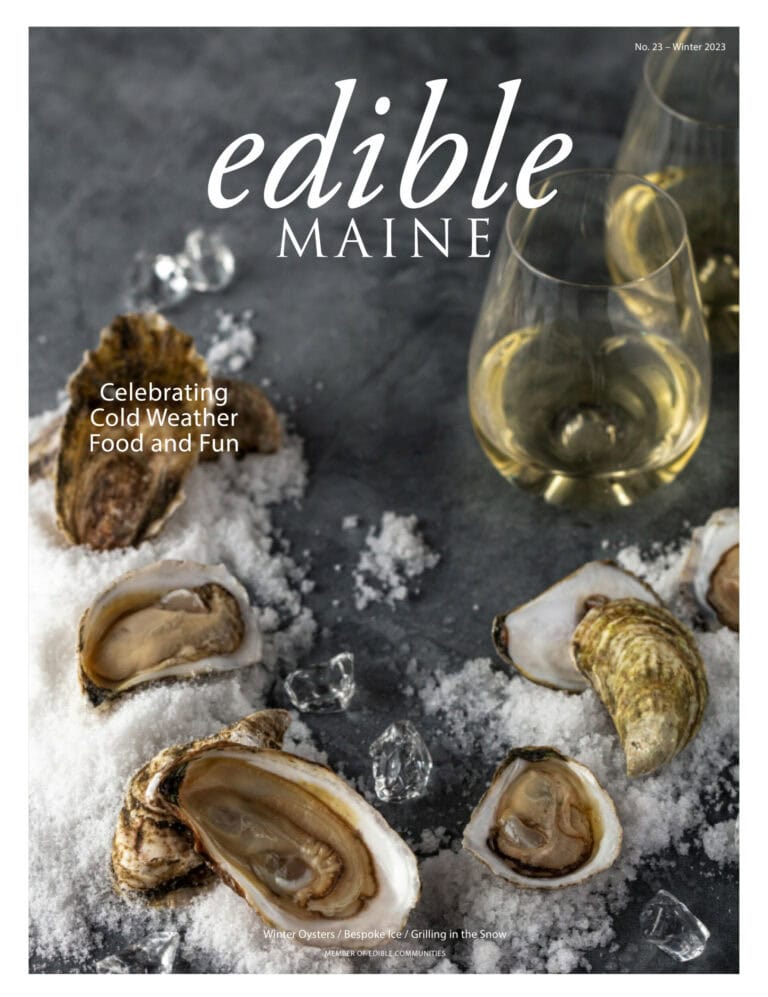

In a state that boasts bountiful harvests from both land and sea, the answer to this question may prove elusive. Maybe you sit firmly on Team Lobster. Or perhaps you stand with Team Wild Blueberry. Team Oyster is coming on strong lately, but you can’t deny the traditional roots of Team Potato or the sweet allure of Team Maple Syrup. These competitors aside, if national market trends hold fast, Team Seaweed may soon surface as a strong contender.

The market revenue for seaweed in the United States is expected to soar to $9.5 billion by 2026, but most (over 95%) of the seaweed consumed in America is currently imported. Maine’s clean waters, coastal lease sites, fisheries infrastructure, and proximity to regional distribution channels give local seaweed producers every advantage to capitalize on the growing market for domestic seaweed, says the recent Edible Seaweed Market Analysis report published by the Island Institute, an organization in Rockland devoted to sustaining Maine’s island and coastal communities. Maine seaweed growers currently produce 60% of the edible seaweed farmed in the United States, an output the Island Institute expects will grow by as much as 15% annually.

Biddeford-based Atlantic Sea Farms (ASF), the first commercial edible seaweed farm in the U.S., is taking advantage of the moment. In 2018, the company produced 30,000 wet pounds of seaweed. This spring the company harvested 1.2 million pounds.

Brooklyn, New York–based Akua, which makes kelp jerky and kelp burgers, currently buys 40,000 pounds of Maine kelp per year, mainly from Summit Point Seafood, a kelp farm in Casco Bay near Falmouth. Akua CEO Courtney Boyd Myers says her company hopes to be buying 500,000, 1.5 million, and 3 million pounds in five, 10, and 15 years, respectively. Myers says the kelp grown in Maine is much higher quality than the kelp imported from Asia. It’s also typically more thick, salty, and meaty than the lighter, crisper, and sweeter kelp grown further south in Connecticut, she says.

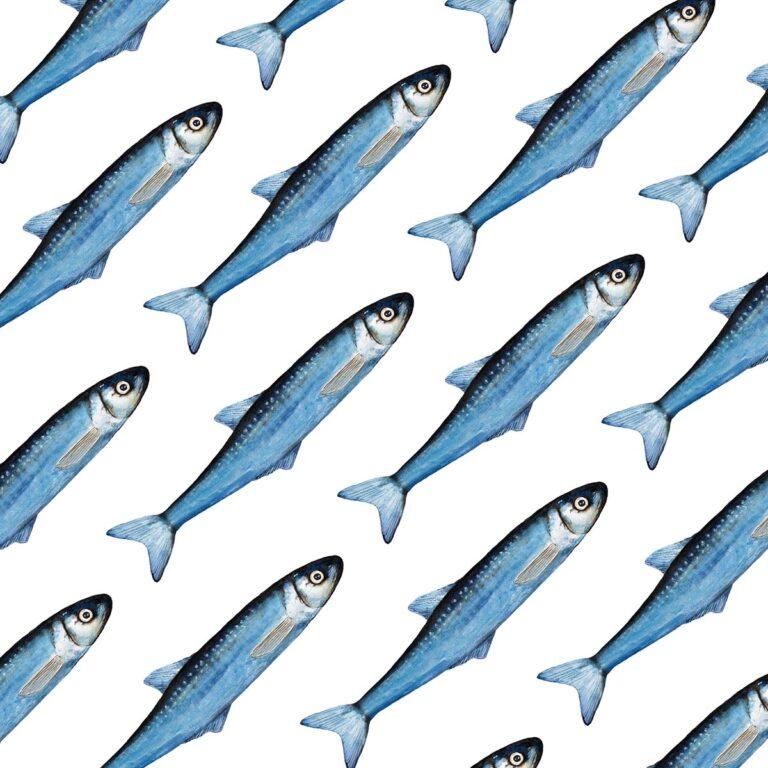

Though many Americans are just now discovering seaweed as an ingredient, it has long been consumed by coastal communities around the world. Seaweed is a staple food in Japan, Korea, and China, and it’s common in the Philippines, several Pacific Island and northern European countries, and the Canadian Maritimes. Coastal Indigenous cultures in North America view seaweed as a natural resource, particularly in the Pacific Northwest. Some anthropologists have argued that the first humans to settle in North America arrived from the Pacific Rim by following a “kelp highway,” eating seaweed to sustain themselves along the way.

Edible algae like alaria, bladderwrack, dulse, laver, sea lettuce, and sugar kelp check all the boxes for health-conscious American consumers. They are low-fat, nutrient-dense, protein-rich, and vegan. Consumers who are concerned with the environmental impact of their foods can embrace seaweed because it requires no fertilizers, pesticides, or fresh water to produce, and it is a regenerative aquaculture crop in that it both sequesters carbon and reduces ocean acidification. Grown in the winter off the Maine coast, the crop dovetails nicely with other Maine fisheries like lobster and groundfish, allowing fishermen to diversify their income without making huge investments in new equipment.

Maine’s seaweed industry now faces the challenge of convincing more Americans to make seaweed a regular part of their diets. Janine Bisaillon-Cary, manager for the MarketShare accelerator program at the Maine Center for Entrepreneurs, says that—as with a lot of ingredients that come from the sea—people have yet to gain comfort with handling seaweed products. “People wonder ‘How do I break open this lobster?’ Or ‘How do I cook this fish?’” Bisaillon-Cary says, noting that “How do I eat seaweed?” is another question along those lines that consumers will need answers to.

Josh Rogers, owner of seaweed tea maker Cup of Sea and Heritage Seaweed, a store devoted to all things seaweed on India Street in Portland, says seaweed adds complex flavor, nutritional properties, and a deep sense of place to Maine food products like his teas.

“Making a delicious product isn’t difficult,” he says, noting that seaweed’s umami flavor is universally appealing. “The challenge is getting consumers to notice it and take a chance on it.”

To that end, enterprising small Maine businesses are rolling out value-added products that make seaweed easier to eat. They are steeping it in teapots, beer cans, and spirit bottles; adding it to ice cream, chocolate bonbons, and energy bars; flaking it dried and flash freezing it for quick additions to salads and smoothies; and mixing it into commonplace pantry items like pasta and tomato sauce.

Biddeford-based Ocean’s Balance takes a straightforward approach to getting customers on board with their seaweed products. “The thought process is always [about] approachability and comfort,” says co-owner Lisa Scali. “We’re putting seaweed into products that people already know and are comfortable with, products that demystify seaweed.” The company’s Chili Lime Seaweed Seasoning, a spice blend with plenty of seaweed but no salt, was awarded a coveted Specialty Food Association’s 2022 sofi Award. Ocean’s Balance offers two types of tomato sauce, Mariner’s Marinara and Mariner’s Arrabbiata, and both get an umami boost from kelp.

Scali says customers are initially drawn to these products, which are carried in over 600 stores across the country, for the story: Ocean’s Balance has partnered with Maine seaweed growers whose kelp improves ocean health. But after that first purchase, customers snap up additional jars for the taste and the easy access to seaweed’s nutritional benefits. “We call [seaweed] Mother Nature’s multivitamin,” says Scali. Seaweed contains antioxidants, omega-3s, iodine, iron, potassium, calcium, and numerous other micronutrients.

Like Ocean’s Balance, Atlantic Sea Farms (ASF) is scaling the seaweed accessibility wall with products tailored for the home cook that are distributed in 1,400 retail outlets nationally. In addition to its ready-to-eat Sea-Chi kimchi, Sea-Beet kraut, and Fermented Seaweed Salad, ASF sells ready-cut frozen kelp and kelp cubes for use as an umami bomb in soups, salads, pestos, and sauces. And it sells smoothie cubes that combine kelp with a variety of fruits, ready for a spin in the blender.

Kelp can go anywhere a green vegetable goes, explains Peter Rahn, director of food quality and innovation at ASF. “It has a crunchy, crisp, fresh flavor and doesn’t taste very oceany.” He says it pairs well with ingredients like ginger, garlic, turmeric, and lemon. ASF plans to roll out center-of-the-plate seaweed options soon, in accordance with consumer trends, he notes. At press time, the company is trialing two types of seaweed burgers – basil pesto and ginger sesame – at Luke’s Lobster in Portland.

Makers of other Maine seaweed products say that using seaweed helps fortify a Maine brand identity.

“When I relocated my creamery to Waldoboro, I wanted to create a cheese with a taste of place,” says cheesemaker Allison Lakin of Lakin’s Gorges Cheese. “I decided to embrace the ‘meroir’ of my saltwater farm and include seaweed in the cheese.” Meroir describes the idea that different temperatures, climates, nutrients, and other geographical factors influence the flavor of marine foods. Lakin’s Rockweed, a soft ripened cheese with a ribbon of dried bladderwrack laced through its center, won a gold medal at the 2022 World Championship Cheese Contest.

Blue Barren Distillery, located on Camden Harbor, bottles a Maine meroir in its sugar kelp vodka. “We wanted the vodka to have a brininess that would pair well with … seafood,” says Blue Barren co-founder Jeremy Howard. He suggests pouring a bit into raw oysters on the half-shell.

When Urban Farm Fermentory owner Eli Cayer travels domestically and abroad, he brings his Portland company’s Seaweed Cidah, a dry-hopped cider made with dulse and sea lettuce, as a sort of Maine ambassador. “It tastes like Casco Bay and finishes like apples,” he says.

In other Maine products, seaweed makes a more subtle appearance. For example, SeaMade’s Cranberry Almond & Kelp Bar starts off sweet (honey and cranberries), finishes salty (the seaweed), and has a very mild kelp flavor. Akua is working with Westbrook’s Mast Landing Brewing Co. to produce a limited-edition Belgian witbier with lemongrass, lime, cayenne, and kelp.

Tortillería Pachanga adds dulse, alaria, and sugar kelp to its organic yellow-and-blue masa blend to produce its blue-green tor-sea-llas. Piccolo Pasta Co. in Portland sells dried pasta flavored with kelp and formed into a frilled, kelp-like shape. The pasta company is headed by chefs Damian Sansonetti and Ilma Lopez, who also own the West End restaurant Chaval. Diners there can enjoy country pâté

that includes kelp as both a flavor booster and a gelling agent. It’s served with pickled kelp stems (called stipes) and homemade kelp brioche.

Portland-based Vena’s Fizz House offers a Rocky Coast Bloody Mary Spirit Sipper mix that contains Maine alaria, dried celery, jalapeño, lemon, and horseradish. Award-winning Rockland-based Bixby Chocolates produces lemon dulse bonbons and sesame kelp truffles, while Biddeford’s Parlor Ice Cream sells a sea salt ice cream laced with chunks of sesame seaweed brittle.

But it’s not just flavor, nutrition, and brand identity that makes seaweed a compelling ingredient for Maine producers; seaweed has other unique properties that are useful in food production. VitaminSea, a family-owned company that harvests and dries seaweed, sells edible flakes, supplements for animals, body products, and even lawn and garden care products containing seaweed. Owner Kelly Roth says the company received a USDA Small Business Innovation Research grant to develop a product called SeaKelp+ that, when added to bread, makes it more nutritious and extends its shelf life by 9–14 days.

Seaweed is also a natural clarifying agent, explains Jon Stein, co-owner of Fogtown Brewing in Ellsworth, who makes a saison called Scupper with a mix of kelp, dulse, and Irish moss. Aside from contributing to a refreshing savory flavor, the seaweed helps to drop cloudy proteins out of the solution and to create a more shelf-stable product.

In an era where green-minded eaters weigh the environmental consequences of their food choices, eating seaweed is unquestionably virtuous: It’s good for us, good for our local economy, and good for the environment. Kelp yourself to the Maine-made products that also happen to taste very, very good.