Artisanal bread baker Barak Olins has created a business that is as mindful and intentional as it is delicious and nourishing. ZU bakery, known for its rustic loaves of bread, has a very loyal following. Just desserts for Olins, who spent over two decades doing the back-breaking work of cutting, splitting, and stacking wood for his oven in Freeport and painstakingly prepping and peddling his products at farmers markets throughout southern Maine.

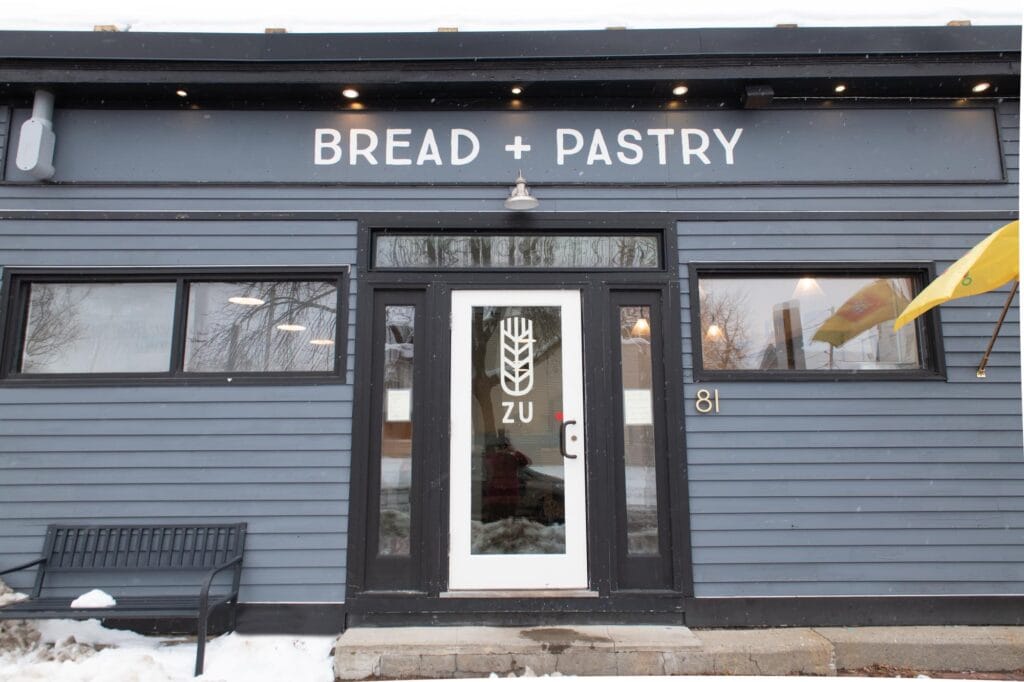

After surviving the exigencies of running a food business through the COVID-19 pandemic, the 55-year-old Olins needed real change. He contemplated what it would mean for him, physically and spiritually, to continue baking. He needed to define how he would age in place as a baker. Today, in a tiny, leased space located at 81 Clark Street in Portland’s West End, Olins thinks he’s got a good handle on the concept.

He wanted to sell his bread from the same place in which he baked it. For himself, the location was physically closer to home and his family. For his customers, he wanted them to serve up the bakery aromas along with the bread.

In March 2022, Olins abandoned his wood-fired oven in Freeport, and his farmers market business, and began designing and renovating his new 650-square-foot space.

“I wanted everything to be efficiently designed—to create a space that is almost a studio, a bread studio,” Olins says.

That studio, which Olins opened in November 2022, has a simple and classic interior meant to evoke the romanticism of a 1930s French bakery. It’s Portland’s first micro-boulangerie. The business plan is grounded in a limited menu of exceptional baked goods sold at fair prices (breads cost between $6 and $10, baguettes are $4, and breakfast pastries run between $4 and $5).

Olins was born in Tennessee; with his parents, who were academics, he traveled the world. In college he studied architecture and African-American literature and history, and then became interested in traditional crafts. He came to Maine because he was intrigued by wooden boat building in Rockport, with its gradual, methodical way of learning the craft buoyed by apprenticeship opportunities. Similarly, Olins intends his bread studio to provide employment opportunities for a few serious bakers whom he will train in his craft.

Olins fell in love with bread baking after opening the now-shuttered Café Uffa in Portland in the 1990s, where he made the bread. “There is something deeply human about working with your hands and having that feedback, whether it’s woodworking or writing.” Or kneading bread, as it turns out.

In 2023, ZU bakery sports a five-deck, electric steam-injection oven that bakes between 80 and 100 loaves at once, up from the 40 his wood-fired oven could handle. All of the whole-grain flour used at ZU is milled in house from Maine-grown grains. Dough is fermented at room temperature in wooden troughs Olins built, then proofed in either banneton (willow baskets) or couche (sheets of folded linen). All the grain used in his baked goods is milled in house. A 100-year-old Belgian-made diving-arm mixer stands to the side, clean and at the ready.

Customers can see, smell, and hear the baking processes in the shop, thanks to its intentionally open floor plan. Olins’ neighbors stop by to let him know they remember his spot as a barber shop, pharmacy, and beauty parlor.

As a concession to baking in place at this stage of his life, Olins has established unconventional hours of operation. When the bakery opens at 9 a.m., Wednesday through Saturday, the coffee’s ready—but there aren’t many baked goods on the shelves yet. Maybe a few pastries, a selection of cookies, some granola. But curiously, no bread.

Olins happily explains that this is one way his establishment differs from a typical bakery. For him to have bread on the shelf by 9 a.m., he would have to be up baking by 3 a.m., something his new work/life balance prohibits. “Rather than having everything available when the doors first open, we have things rolling out all day [long]; we’re in production mode all day.” That means mid-morning customers get a croissant that came out of the oven 20 minutes ago, instead of six or eight hours ago. A baguette or loaf of bread you buy at lunchtime may still be warm, or even hot out of the oven.

“We are not a culture that demands fresh bread at 8 a.m., generally,” says Olins.

He thinks his schedule fits American tastes better—something sweet in the morning and bread to go with dinner. The setup works for him. And as we’re the beneficiaries of these artisanal baked goods, it can work for us, too.

For more information go to zubakery.com.