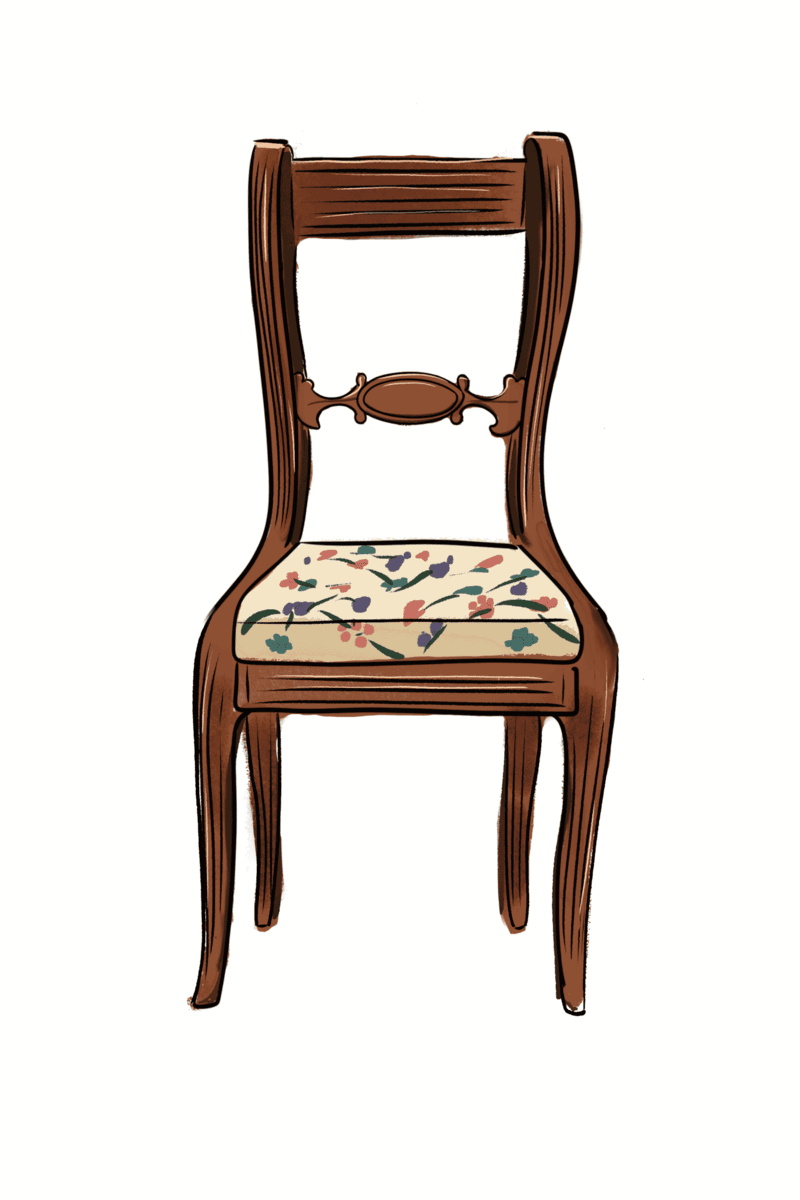

Next to my bedroom door, there is a chair. It is solid wood, with curved legs and a curved back. Long, even grooves run up and down the wood like railroad tracks, giving it an elegant, geometric look. It is made of oak, except for the seat, which is upholstered with a floral cloth in muted beige, brown, and green tones.

The chair used to be part of a dining set in my grandparents’ house in Albany, New York. They were solidly middle class, but they had some fine furniture. My grandfather was an experienced woodworker who could make, select, and repair strong pieces. His legacy is sealed with wax and linseed oil.

My grandma fell and broke her hip in the fall of 2020 and passed away days later. My mother, knowing how much I loved wood furniture, put this chair aside for me. When I received it months later, I teared up because it had been part of my childhood. Even though it now stands alone, the chair holds memories of many Easter dinners in my grandparents’ home with its dogwood bushes, needlepoint artwork, and 1970s tiles. I love it for those reasons, and because it is beautiful.

Without its companions, I don’t use this chair when dining. I prefer to contemplate it as an art object—a memory chair. Yet for decades, it served a function in a classic dining room, in its place, with others like it, around a matching table. Today I know so few adults who have dining rooms. If they sit at a table at all to eat, it’s most likely in the kitchen.

Where you sit at table has historically mattered. Back in medieval Europe, only nobles sat in chairs. The big, boxy throne was the best seat in the house. Everyone else perched on benches or stools. To have your back supported showed privilege.

In 17th century France, craftsmen created lighter, smaller, more mobile chairs. Because the French nobility set the standard for European fine dining, particularly when it came to the accessories, these more demure but still ornate chairs were codified as part of a mannered meal. European neighbors put their own marks on their chairs, though. German chairs, for example, were clunky but still as ornate. English chairs were less curvy and sensuous, more dour.

In the forested Maine landscape of the 1800s, many of the glorious hardwood trees were destined to become world-class chairs. Back then, Shaker furniture set the standard for American craftsmanship. These chairs were simple and restrained, though no less sturdy. Built with utmost care, Shaker ladder-back chairs had little embellishment, save for thick coatings of milk paint in traditional colors (mustard yellow, falu red, pine green, and cornflower blue). Some, though, were left in their natural state, finished with only wax and oil. You can see the originals in situ at the Sabbathday Lake compound in New Gloucester. There, a small group of Shakers still live the handcrafted lifestyle, though they no longer manufacture furniture themselves.

The fingerprints of classic Shaker chairmaking are evident in most modern furniture stores. The Shakers influenced Danish modernist designers like Hans Wegner and Børge Mogensen, acclaimed Japanese American designer George Nakashima, and the Maine-based furniture masters at Thos. Moser and at Chilton Furniture.

I covet the subtle curves of the Thos. Moser Edo dining chair. Someday, I’ve promised myself, I’ll buy one to sit alongside my grandmother’s chair. That purchase may kickstart my future collection of Maine chairs, pieces that are made locally and tell the story of my chosen home. I could stock my dining room with pieces from Chilton and Thos. Moser and buy others from lesser-known design-build shops like Maine Woodworks, which has a social mission of supporting employees with special needs, or Wayne Hall of Bucksport, who has a more rustic style. I could also shop bespoke furniture makers like Heide Martin Design Studio in Rockland, Kidwell Fabrications in Portland, Gabriel Keith Sutton and Corbin Design & Fabrication in Biddeford, and Bicyclette Furniture in Brunswick.

Right now, my kitchen table is surrounded by a motley crew of simple seats. There are two cross-back cherrywood chairs and a black-painted antique with turned legs I bought at an estate sale. I have a couple of midcentury modern bentwood-and-wire chairs I picked up at the Portland Flea-for-All, and a single Ikea chair I bought in college. They don’t match, but they are interesting and still somehow cohesive. They follow the same basic design principles established centuries ago, and together they tell the story of my movements in life.

But as a matter of course, I know there will always be a place at my table for one more, especially one made in Maine.