Tourism and hospitality students at the University of Southern Maine (USM) are making cross-cultural connections via ingredients that are both close to home—and worlds away—by studying indigenous foodways with the Wabanaki nation here in Maine and the Inuit people of Greenland on their home turf.

This collaboration, which will culminate in a cookbook called A Taste of Two Worlds, is funded by the Arctic Education Alliance, a U.S. Department of State initiative that helps Greenlandic and American schools grow educational opportunities that focus on land and fishery management, sustainable tourism, and hospitality.

“The world is showing a lot of interest in Greenland, and we have to be ready for whomever comes,” says Aaju Simonsen, a principal investigator at the Arctic Education Alliance in Nuuk, Greenland. She emphasizes the importance of collaborations of all types. “One of the main tasks of the Arctic Education Alliance is to open up pathways for the next generation.”

One pathway involves exploring culinary traditions in a project called “A Taste of Two Worlds.” In May, a group of USM students and members of the Wabanaki nation visited Greenland for a hands-on experience in the indigenous foodways there.

“Gathering should be celebrated by making those connections and working to revitalize our traditional foods,” says Andrea Sockabasin, Community and Land Wellness division director at Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness.

The goal is for students from USM and the Inuili Food College in Narsaq, Greenland, “to see their food systems in a different way and prepare, plan, and prep food for one another that showcases a ‘taste of place,’” says Kristin Fuhrmann-Simmons, a USM instructor who teaches local food and agritourism courses.

While in Greenland, the students spent two weeks traveling via helicopter, airplane, utility terrain vehicle, and boat to explore the communities and fjords of southern Greenland. They built relationships with local college students and folks involved in sustainable tourism initiatives, like natural hot springs and ruins of Inuit and Viking settlements. The visitors explored the local food system by visiting traditional sheep farms and experimental fruit and vegetable farms designed to expand local food production.

During their travels, participants expanded their palates with forays into local cuisine that included polar bear, seal, muktuk (narwhal), reindeer, musk ox, and fermented seal blubber. A local family in the port city of Qaqortoq hosted a kaffemik, a social gathering where traditional dishes including halibut, minke whale, salmon, thick-billed murre (sea duck), and crowberries were served.

In the seaside town of Narsaq, they witnessed an ancient tradition among the Greenlandic Inuit where hunters land and butcher a walrus—a community event for all ages that pays respect to the ocean as a source of sustenance.

“We saw the whole community come together [to see the walrus]—with the youth learning from the elders,” says Saige Purser, director of Our Future Generations at Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness. “We had the opportunity to be part of that and to see it, and that felt like home. There was a real connection there.”

“Some of our traditional foods can be controversial. We’re no longer able to access some of those foods due to pollution, hunting restrictions, and climate change,” says Lauren Stevens, Culture, Connection and Support division director at Wabanaki Public Health and Wellness. “When you’re able to share that traditional cultural experience, it’s deeper than just eating. It’s a deeper connection to the land and to one another and our ancestors.”

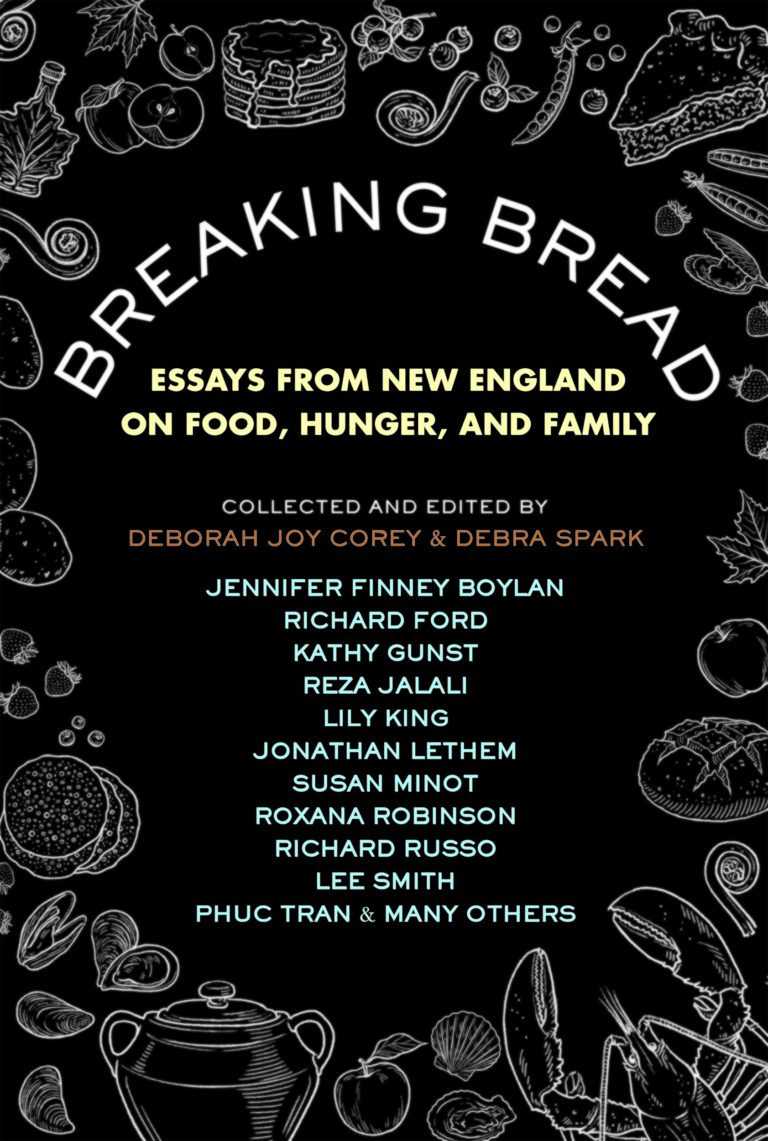

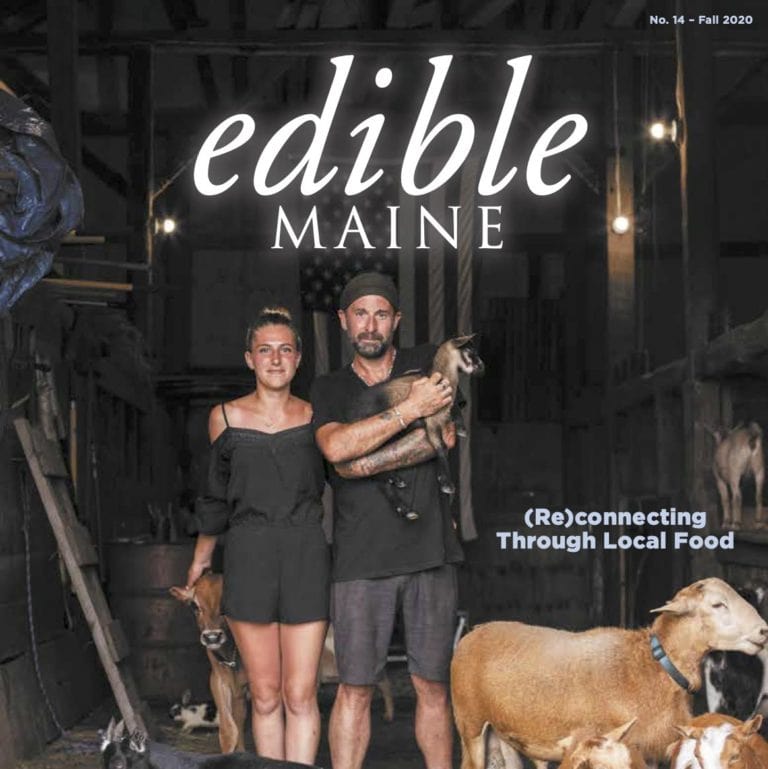

In the kitchens at Inuili Food College, the students crafted recipes with ingredients and inspiration from near and far; their work will be included in a cookbook set to be published with the technical assistance of edible MAINE. The cookbook will emphasize the seasonality of traditional foods and the connection to land and sea. Its recipes will feature locally sourced game, berries, shellfish, and root vegetables from Wabanaki communities; lobster, mussels, monkfish, and kelp from Southern Maine; and snow crab, musk ox, lamb, reindeer, and salmon from Greenland.

Prior to the Greenland trip, USM students participated in collaborative cooking workshops with Wabanaki partners, as well as chefs in the Portland area. “We talked about breaking down a moose, butchering it, and making sausage,” says Johanna Piekart, a USM junior and culinary intern with the project.

While participants are from places that are oceans apart, many conditions are the same, says USM senior Vanessa Bauque, who hails from South Africa. “For [the Wabanaki], if you’re going to eat something, you’re going to finish it. My culture [the Zulu culture] is like that, as well. If you’re going to slaughter a cow, you have to use the whole cow. It’s a soul. You’re taking something from the world.”

Simonsen, a Greenlandic Inuit, says her grandfather hunted from a kayak. He would carry a bottle of fresh water with him so that when he killed a seal, he could give it a drink of water to pay his respects and send the soul of the seal to a better place.

“In sharing space with students, we’ve learned there are many similarities between cultures and experiences—that strengthens our relationships, but it’s also knowing there’s so much room for growth,” says Purser, who would like to bring Greenland Inuit and Wabanaki youth together in the future.

“Sharing food is sharing culture, which is sharing medicine,” says Stevens. “That is good medicine.”