Maine native Jesse Souza is not a schoolteacher, but he is an educator of sorts. As the executive chef at Front & Main Restaurant in Waterville, he aims to serve delicious food to every customer of the approachably chic eatery on the ground floor of the Lockwood Hotel, a $26 million facility funded by Colby College and named after a historical textile mill.

Souza, wooed home from a career in the Pacific Northwest by family ties and the prospect of cooking elevated Maine comfort food, consistently hits his mark. He and his eight-member kitchen crew do so with help from Maine’s farmers and fishermen, cheese producers and grain millers, bread bakers, and potato chip makers.

Toasted barley risotto with scallops, sautéed mushrooms, roasted cauliflower, butternut squash, and ricotta and parmesan Reggiano cheeses

A. The Maine scallop fishery is a seafood management success story.

B. Heritage grains feed both Mainers and the state’s beer industry.

C. Mushrooms are cultivated year-round in Maine.

For home cooks shopping retail, finding Maine ingredients is easy these days. On-farm, contact-free stands sprang up during COVID-19 and remain open today. A hundred seasonal farmers markets dot the map May through November; two dozen operate indoors all winter long. Independent grocery stores and supermarket chains stock products like Gulf of Maine haddock, native blueberries from Downeast, Aroostook County potatoes, and mushrooms cultivated indoors in Springvale.

For restaurants, though, sourcing Maine ingredients with the consistency required to maintain customer satisfaction can be difficult. Chefs can shop the farmers markets, and farmers can deliver their food directly to restaurant kitchens, but neither practice scales well in the fast-paced restaurant space or the time-crunched farming community—especially with the staffing and margin challenges in both sectors. Restaurants need cooperative, resilient methods to get ingredients into their kitchens quickly and without waste. At edible MAINE, we call this developing distribution system “Local Food 2.0.”

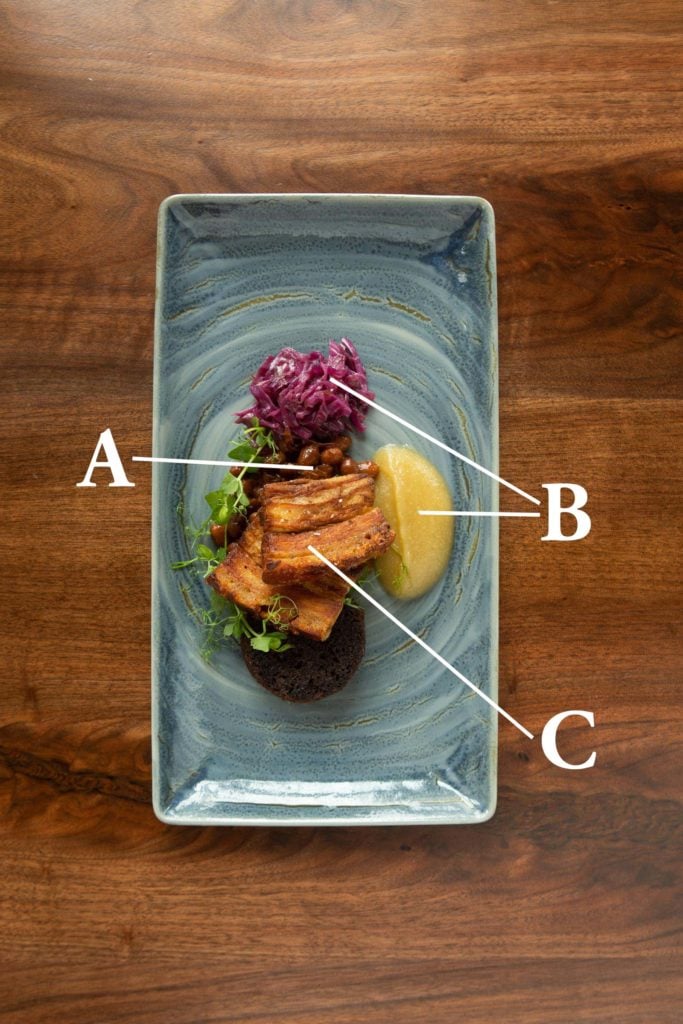

Pork & beans with heritage pork belly, bourbon applesauce, steamed brown bread, red cabbage, and maple baked beans

A. As a rotational crop, beans fix soil depleted by wheat crops.

B. Cabbage and apples store well for year-round availability.

C. Flavorful locally raised pork satisfies eaters with right-sized portions

Months before he hired Souza, Lockwood Hotel General Manager Jordan Rowan cold-called farms, creameries, breweries, bakeries, and Maine-based distributors like Crown O’Maine in Vassalboro and Native Maine Produce in Westbrook to learn which ones might fit into the restaurant’s plan to dominate every plate with local food. Souza received this list when he came on board 90 days before Front & Main’s soft opening in March. From there, Souza made his product selections and crafted the menu.

“We want diners to enjoy their food without having to be overeducated about it,” says Rowan. But he doesn’t deny the teachings on display with every plate.

For one, most animal proteins served at Front & Main are raised on Maine pastures or pulled from Gulf of Maine waters. The pork comes from Broad Arrow Farm in Bristol, the chicken from Common Wealth Poultry in Gardiner, and the ground meat from the Rowbottom family farm in Norridgewock, with rotating Maine fish and shellfish offerings collated and delivered by Harbor Fish in Portland. The scallops topping some of Souza’s risotto dishes are available because of Maine fishermen’s sustainable seafood management plans. The ribeye steak, a lone exception, is sourced from away to keep its menu price down, but it’s also been the only item affected by disruptions in the national meat distribution chain. Local meats have been consistently delivered as expected, says Rowan.

Souza loads his bar, dinner, and brunch menus with Maine fruits and vegetables. There are Maine potatoes and house-made cucumber pickles with his gluten-free fried chicken, for example. But since the restaurant is experiencing its first harvest season—one encompassing a spring drought followed by deluging summer rains—supplies of local produce have been wonky. “Strawberries were late. And the mushrooms coming in after the rains were unbelievable,” says Rowan, adding he expects his team will get used to the Maine crop ebb and flow and adjust accordingly.

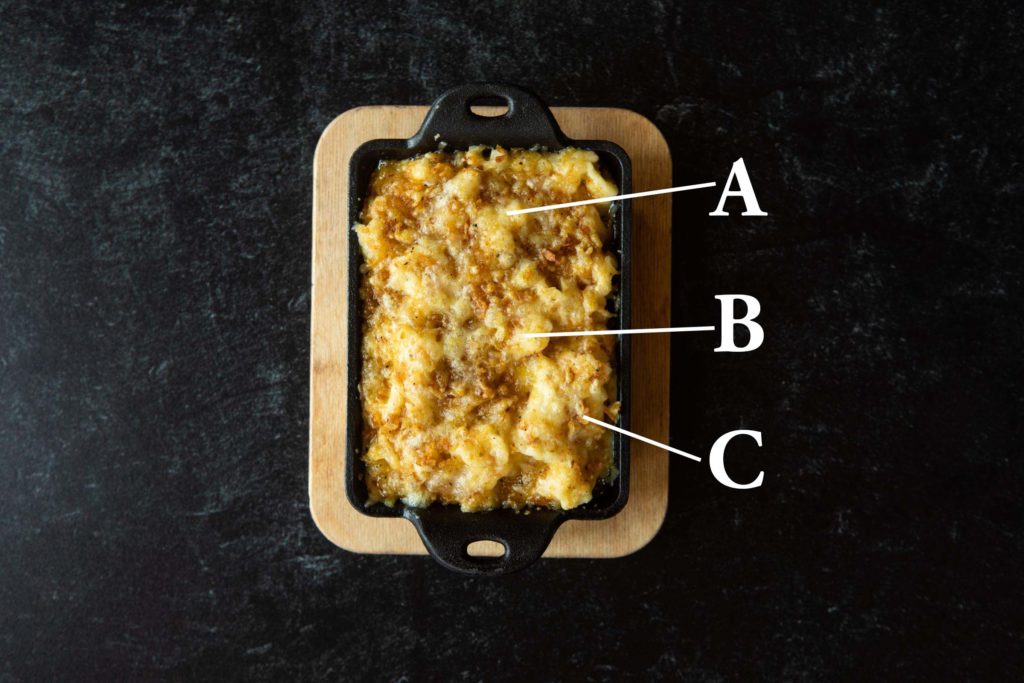

Kids mac & cheese with local pasta, raclette, and potato chip crust

A. Cheese production bolsters the state’s dairy industry.

B. Maine-made pasta curbs food mile tallies.

C. Chips are a value-added product made from Maine spuds.

Meanwhile, the distribution channels for Maine-produced beans and grains, cheeses, and pantry items are flowing consistently. Rowan is unabashedly impressed with the Maine Grains operation in Skowhegan. Headed by Founder and CEO Amber Lambke, the company connects wheat, barley, and oat growers in Maine with chefs, cooks, and bakers throughout New England and New York. Souza taps Maine Grains’ black barley in his risotto and their dried marfax beans for his pork and beans. Grain farmers plant these beans as a rotational crop to help fix soil depleted by wheat production.

Crispy fried chicken with peas & carrots, potatoes, pickles, and hot maple honey

A. Honey and maple syrup are local alternatives to processed white sugar.

B. Pickling preserves peak-season flavor for future use.

C. Maine meat production drives increased local processing capacity.

Maine-grown grains also feature in Front & Main’s bar program. All pilsners, IPAs, wheat beers, and lagers on tap (plus many in bottles and cans) come from Maine brewers, many of whom use local grains. And Souza is still experimenting with which Maine bourbon or rye works best in his whisky applesauce.

Finally, understanding the importance of local cheesemakers, Souza taps Crooked Face Creamery for the ricotta in his risotto and the aged raclette in his mac and cheese (served plain to kids or with chorizo and Maine crabmeat to adults). The macaroni in the cast-iron serving dishes comes from Nomad Pasta in Belfast, and the topping comes from Fox Family’s Salt and Pepper potato chips made in Blaine.

At every turn, eating at Front & Main gives you a taste of how Maine’s value-added producers can add substance, flavor, and texture to your life. There are many lessons you can learn from the food served here and the myriad other independent Maine restaurants that tap into the evolving local food system. Start studying.