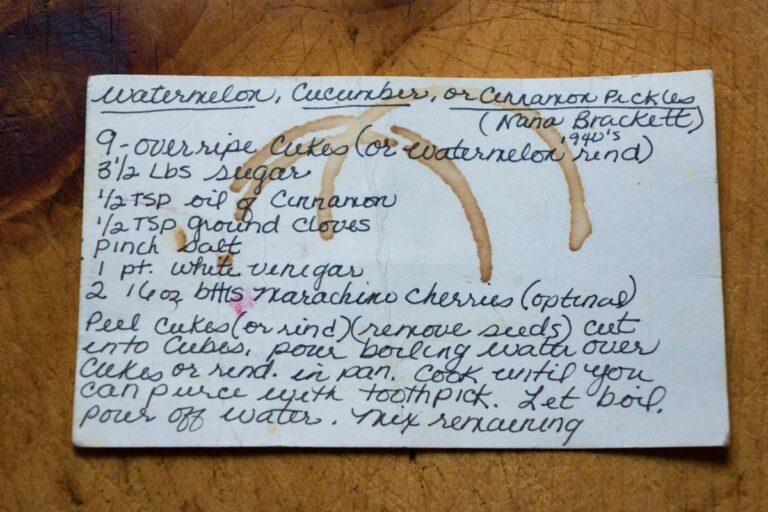

Editor’s note: Both scientific data and governmental policies concerning PFAS exposure are evolving rapidly. The information reported here was current at press time in mid-August 2022. Check back for updates.

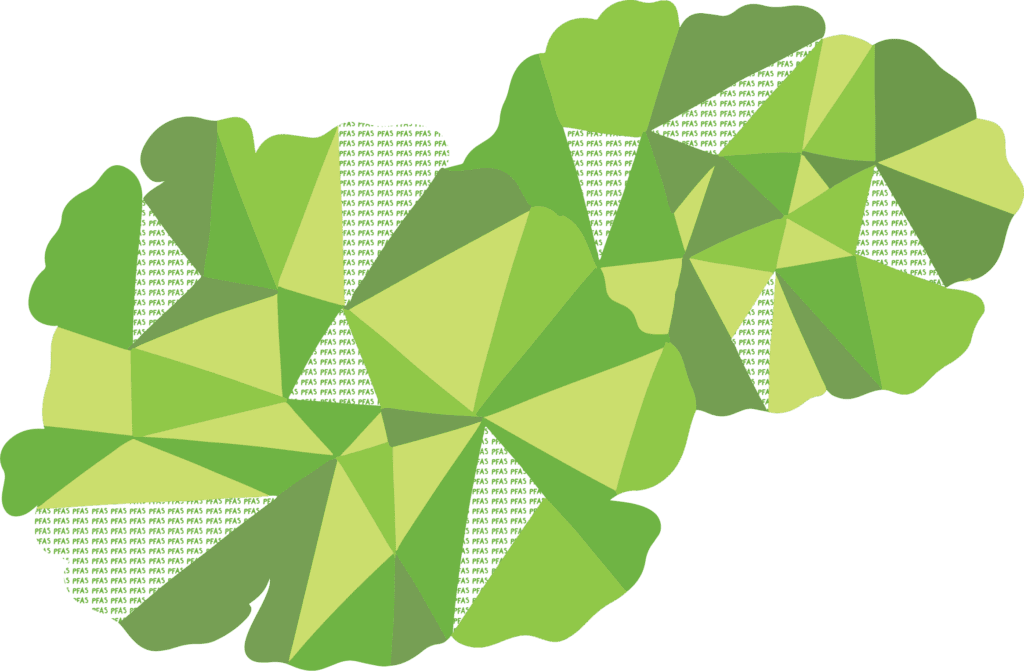

While nothing lasts forever, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) come frighteningly close since they cycle through the environment almost indefinitely. This group of more than 9,000 synthetic chemicals presents assorted human health risks. In children, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports, studies have found developmental effects such as low birth weights, accelerated puberty, and bone variations; a few studies have also drawn weaker associations between PFAS and behavioral changes like hyperactivity.

Because PFAS have exceptional resistance to heat, oil, and water, they first appeared in products like Teflon cookware, Scotchgard-treated rugs, and firefighting foam. Now they’re used in everything from windbreakers to dental floss. Anything labeled “stain-resistant” or “waterproof” is likely to have PFAS, but countless other items are also likely to have them—due in part to PFAS being used in manufacturing equipment.

Commonly dubbed “forever chemicals,” PFAS are now in many public drinking water supplies, and preliminary testing has found them in some vegetables, grains, milk, beef, seltzers, deer meat, and freshwater fish. Certain types of food packaging, such as microwavable popcorn bags, takeout containers, and fast food and bakery wrappers, have tested high in PFAS. And because PFAS are highly mobile, they can migrate from packaging into food.

Maine is at the forefront of states testing for PFAS, so it might appear to have more contaminated foods simply because it’s paying closer attention to the issue. But PFAS are an international concern and likely affect many domestic and imported foods. Buying local Maine foods may help minimize exposure because the state—unlike most others—has begun testing some products and pulling contaminated items from the market. In addition, many small farms in Maine have been working to protect their customers.

PFAS have already shown up in 98% of blood samples, according to results from a national testing program. In June, the EPA dramatically lowered its recommended drinking water exposure levels for two of the most common PFAS chemicals: perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS). The EPA’s health advisory tightened the recommended levels from 70 parts per trillion (previous guidance from 2016) to 0.004 parts per trillion for PFOA and 0.02 parts per trillion for PFOS, reflecting growing evidence of health concerns. One part per trillion is often likened to a single drop in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools, and the new guidelines set levels below what can currently be measured.

Parents now have ample cause for concern but a dearth of data on how best to limit their family’s exposure. Here are current answers to some of the pressing questions parents may have.

Why worry about PFAS exposure?

“Forever chemicals” can accumulate in plant and animal tissue, becoming more concentrated as they move up the food web, where risks to humans come primarily from ingesting PFAS in food and water. Exposure begins early in life. A preliminary study conducted in China, published in the journal Environmental Pollution, showed that all of the 54 placentas tested had detectable levels of PFAS. Testing conducted by the United States and Canadian governments has confirmed that the chemicals pass from mothers to infants in breast milk.

Children are at higher risk from exposure to PFAS than adults because they ingest more food and water per pound of body weight. Preliminary research suggests that higher blood levels of PFAS appear in children whose diets are high in packaged foods, fast food, and fish harvested from contaminated waterways.

Health studies are still confined to a few dozen of the PFAS compounds manufactured. Even this limited sample reveals a range of risks that include decreased vaccine response in children, numerous cancers, increased cholesterol, endocrine disruption, weakened immune systems, ulcerative colitis, liver damage, and high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia in pregnancy.

There is no established treatment for PFAS exposure, but recent guidance from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine now recommend testing of PFAS blood levels for those who have had high exposure (either through occupational hazards, a contaminated public water supply or a private well situated near a potential contamination site—like an airport, military base or landfill).. Humans can excrete PFAS slowly, over years, but exposure can outpace the body’s ability to expel them.

How do PFAS enter the food web?

One major entry point for PFAS into food systems is through the long-standing practice of spreading sewage or industrial sludge containing the chemicals on farms. Roughly half of the nation’s wastewater sludge is land-applied, and PFAS may have affected more than 20 million acres of U.S. farmland.

This year, Maine became the first state to ban sludge-spreading and the sale of sludge-based composts, helping limit further contamination of farm soils. The Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has begun testing soils and waters at more than 700 sites that were historically permitted for sludge or septage applications, starting with the locations thought to be most contaminated. As of June 1, the DEP had tested more than 800 wells, 32% of which registered PFAS levels over the state’s current drinking water standard (of 20 parts per trillion for any of six PFAS chemicals). The agency expects the testing process to continue through 2025.

What testing is underway for PFAS in food?

A risk assessment published in 2020 by the European Food Safety Authority found that consuming fish meat, fruits and fruit products, and eggs and egg products contributes to PFAS exposure.

Despite PFAS being produced for more than 70 years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) admits that the scientific understanding and technical instrumentation needed to test for PFAS at very low concentrations in food have only recently begun to emerge. The FDA has done limited sampling of foods for 16 chemicals but has not yet set any PFAS food safety thresholds. The Maine Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), therefore, has to do the research needed to set state action levels. So far, the Maine CDC has done this testing for milk and beef. Products that test above current levels are disposed of.

As we learn more about PFAS health effects, toxicologists are ratcheting down recommended exposure levels. In response to revised federal toxicology data, Maine may markedly lower its action levels, according to a presentation by the state toxicologist earlier this year.

With funding from the state, researchers at the University of Maine have begun to assess how PFAS move in soils and get taken up into different plants. Many variables affect that process, from the kind of PFAS chemical to the soil type and crop type. In early research, PFAS uptake appears highest in leafy greens and the vegetated portions of plants like grains, tomato, cucumber, carrot, and potato, rather than in the root, fruit, or grain portions.

How can my family minimize PFAS exposure until more is known?

Even as research proceeds, you can take actions to help limit your family’s exposure to PFAS:

- If you drink well water, check Maine’s sludge and septage permit map to see if your property is near a historical application site. Water testing information can be found on the DEP website.

- If your public water supply contains PFAS (all districts must report this information to the state by the end of 2022), consider water filter options.

- Keep children off stain-treated carpets. The federal CDC notes that the greatest exposure to PFOA and PFOS for most infants and toddlers involves hand-to-mouth activities on these surfaces.

- Avoid non-stick cookware; use seasoned cast-iron skillets instead.

- Certified organic farms are not allowed to spread sludge, but because PFAS are persistent and mobile, past sludge-spreading—even on neighboring lands—may still affect products from these farms. Ask food producers about whether they’ve tested for PFAS.

- Consider supporting the Maine farms that have been affected by PFAS contamination, often due to practices on their land long before they owned it. Maine Farmland Trust and the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association jointly administer a PFAS Emergency Relief Fund that is supplementing funds the legislature approved to help affected farmers.

- Avoid food packaging known to contain PFAS, such as microwavable popcorn bags, fast food packaging, takeout containers, and coated pizza boxes.

- Follow Maine’s fish consumption advisories and try to avoid buying fish harvested in highly contaminated areas.

- Follow deer consumption advisories for PFAS outlined by the state.

- If you previously bought substantial amounts of sludge-based compost for your home vegetable garden, review the University of Maine Cooperative Extension’s “Understanding PFAS and Your Home Garden” website.

- Seek PFAS-free options for common household products, outdoor gear, and other clothing. Maine has enacted a ban on intentionally added PFAS in products, but it won’t take full effect until 2030.