Sonya Raab’s description of baking sourdough is blunt and visceral. “It’s a full-time relationship because you can’t turn away. You feed it every day until it becomes alive and active. Then it’s forever—unless you kill it,” she says. In 2020, recovering from surgery and furloughed from her restaurant job in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, Raab decided it was time to become, as she puts it, “a good Jewish bubbie” and learn to bake something. That something was sourdough.

In her cramped apartment, Raab realized that, even on crutches, she could maneuver in the kitchen. What followed were daily experiments—resulting in, she recalls with a laugh, “a lot of really bad bread.” What she couldn’t eat she gave away, but what began as a hobby quickly became something more. On her first day of sales, she sold out. “It blew up from there.”

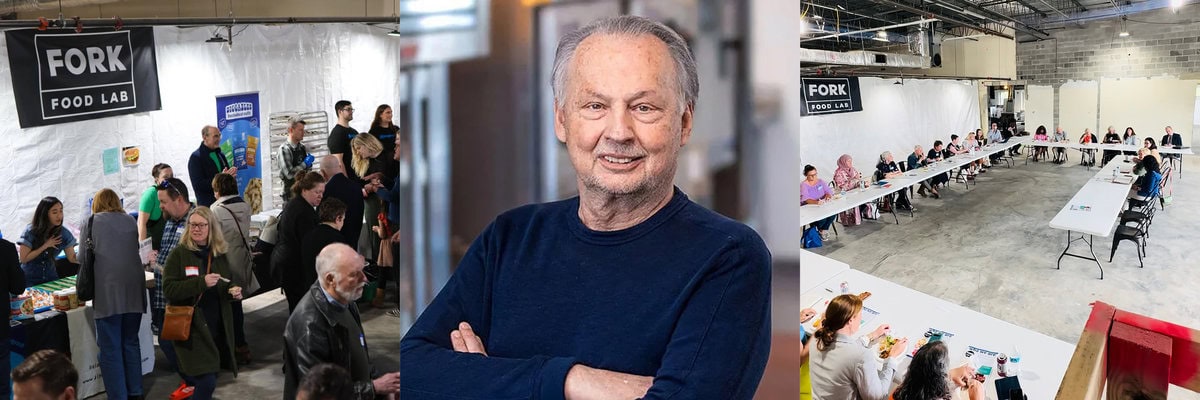

Raab was part of a wave of roughly 20,000 people who migrated to Maine during the pandemic. “I drove straight to Fork Food Lab to meet with Corinne,” she says. Fork, a shared kitchen incubator in Portland, opened in 2016 to reduce the steep startup costs faced by food entrepreneurs. “We provide the opportunity for businesses to not only get started, but to grow and scale,” says Corinne Tompkins, Fork’s deputy executive director.

Bread and Blossom, Raab’s company, now churns out sourdough rolls, brioche buns, pretzels, and pizza dough from Fork’s facility, selling directly to consumers at farmers markets.

Raab’s story, while inspiring, is far from unique at Fork. Entrepreneurs from all walks of life have found a home in this collaborative kitchen space. Among them is Stella Sarros, who, like Raab, made the move to Maine during the pandemic. Furloughed from a Disney resort in Hawaii, Sarros and her husband, Maki Terzopoulos, yearned for a more affordable place to launch their own business, one closer to their Greek roots. “Whenever we’d call to get a brick and mortar of our own, we always had ‘no’s, like a no answer or ridiculous rent,” says Sarros. But when she contacted Fork Food Lab, the answer was different. “It was the first ‘yes.’”

The couple launched Hellenic Kitchen at Fork, bringing Greek comfort food to Maine. The dishes, rooted in family recipes, include pastitsio, a decadent mac n’ cheese, and moussaka, an eggplant lasagna topped with creamy bechamel made from Kefalograviera, a sheep and goat milk cheese sourced from Greece. While their ingredients are distinctly Greek, Sarros notes that much of what they use is sourced locally. “Our food tastes so much better than in Hawaii,” she says. “The cost is actually lower, so we’re saving money but getting the best quality.”

In many ways, Fork Food Lab is a microcosm of Maine’s food landscape, where local sourcing meets international flavors. In its nearly eight years of operation, Fork has helped launch almost 300 businesses, showcasing cuisines from 16 countries. Tompkins sees an increasing demand for culturally appropriate food from Maine’s growing refugee, immigrant, and asylum-seeking communities. “We’re going to see a rising trend of culturally appropriate food,” she predicts.

Fork has partnered with the Maine Immigrants’ Rights Coalition to produce meals for newly arrived Mainers living in hotels along Route 1. “Cooking food is not the end goal. It’s having their own business,” says Tompkins. At any given time, 40 to 50 entrepreneurs are waiting to join Fork’s roster. “They’re in the wings, sending me emails, figuring out next steps.”

Waiting in those wings was Caitlin Houser, who stumbled on her business idea after seeing a neighbor’s milk bottle delivery. “What if we brought pre-batch cocktails to people’s doors?” she wondered. But when Houser looked into the logistics, she found that Maine’s liquor laws made her concept untenable. “I wanted to purchase spirits, open said spirits, mix said spirits, repackage said spirits, and then deliver said spirits, and that’s just not okay here,” she says.

Undeterred, Houser launched The Milk Bottle in 2021, producing cocktail mixers that could be paired with spirits at home. Her seasonal collaborations highlight local ingredients, such as Husk Cherry Honey Lemonade with Liberation Farms and Watermelon & Basil with Hunnewell Farms. Winter brings Blueberry Snap Punch and Cranberry Rosemary Orange, mixers that pair beautifully with tequila, bourbon, gin, champagne, or even seltzer.

“A lot of people have minds for math, grants, words, dentistry, banking,” says Houser. “I dream about food and flavor.”

Another entrepreneur with a passion for ingredients is Kat Jordan, whose business, Kittylamb, emerged from a personal health crisis. Facing a debilitating illness in college, Jordan researched food labels and cut out anything artificial. “I completely changed what I ate and turned my life around,” she says. Jordan saw a market need for elevated baking mixes made with clean, organic ingredients. After a year of experimentation, Kittylamb was born—a line of baking mixes with ingredients like fair-trade chocolate and real vanilla extract. Searching for production space, Jordan found Fork’s month-to-month leasing terms and supportive community a perfect fit. “They were the first people I made those brownies for,” she says of Fork’s members.

Fork’s ecosystem extends beyond its four walls, offering connections to resources across Maine. “Before you get started, we provide a service unique in New England that evaluates each person individually,” says Tompkins. “What is their product? What are their services? How are they going to make money? Then we connect them with a strategic network.”

For some, like Hannah Lake White, Fork became the lifeline that allowed her business to survive the pandemic. White had envisioned Lake & Co. as a boutique catering business, but when COVID hit, she pivoted to prepared and frozen meals. Fork’s flexible space allowed her to keep overhead low and her operation nimble. “No one knew COVID was going to happen. But the fact I was there was a miracle because I didn’t have overhead and slid under the radar,” she says.

Lake & Co.’s bestseller is reserved for winter: a chicken pot pie made with chicken poached in white wine, bay leaves, and lemon, then baked in a buttery pie dough. The success of her meals eventually led White to outgrow Fork. In 2023, she and her team moved into a 3,000-square-foot space in Yarmouth. “It felt very much like, ‘I know I have to spread my wings and enter the bigger world on my own,’” says White. But the relationships forged at Fork remain intact. “We’ve built this community who have ordered every week since the beginning.”

Fork’s model doesn’t guarantee success, but it provides the tools and opportunities for those willing to take the leap. “We don’t pick winners,” says Bill Seretta, Fork’s executive director. “We provide the opportunity. They have to decide what to do with it.”

As Fork continues to expand—its 42,000-square-foot footprint includes a new meat and vegetable processing facility—it’s clear that this kitchen incubator is more than just a space. It’s a launchpad for Maine’s food entrepreneurs to build businesses, grow communities, and, ultimately, create new opportunities for themselves and others.