Add nothing to the wine.

And take nothing from the wine.

Those are the basic tenets of the modern natural wine movement that began in France in the 1950s when celebrated wine scientist Jules Chauvet started experimenting with making wine with zero added sulfites.

The culture of natural wine has since spread across the globe, settling comfortably onto shelves in wine shops, into glasses at wine bars, inside wine club boxes, and as a theme for wine festivals. Sometimes referred to as biodynamic, low-intervention, raw, naked, or natty wines, these products have captured the imagination of wine drinkers open to new flavors, textures, and levels of effervescence.

The list of additives that go into mass-market, conventional wines is long, explains French wine writer Aaron Ayscough in his book The World of Natural Wine. There are acidifiers (tartaric acid), clarifying agents (egg whites and pea proteins), colorants (concentrated grape juice), deacidifiers (lactic acid bacteria), decolorants (activated charcoal), enriching agents (sugar, oak chips), fermentation aids (ammonium bisulphate and sulphate), and preservatives (carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide). Not only do natural winemakers eschew additives during the winemaking process, but they also start the process with grapes grown sans chemicals and harvested by hand to keep natural yeasts in play.

Oyster River Winegrowers, a small farm winery in Warren, has been making low-intervention wines since 2007 with organic grapes grown on site and sourced from other growers in the Northeast. Winemaker Brian Smith believes his role in winemaking is to be more nature’s assistant and less chemistry wizard. Most of Oyster River Winegrowers’ fermentations start spontaneously with wild yeasts that occur on the fruit and in the cellar. All its sparkling wines (called Chaos and Morphos) are bottled without sulfites and are not filtered. In rare cases, the winery’s still wines are minimally sulfited, but only when absolutely necessary, explains Smith.

So how does a drinker know when they are getting a natural wine? Most winemakers approaching their craft in this fashion are transparent about it, explaining their processes to visitors in person and outlining them on websites. But that information isn’t always spelled out on the label. European winemakers will be required later this year to start listing ingredients on their labels, but U.S. winemakers aren’t yet required to disclose any ingredients in the mix. Colorado-based Clean Label Project does offer a third-party certification—think of the “certified organic” stamp on a jug of milk or a Marine Stewardship Council label on a bag of shrimp—for natural wine. At press time, only one company, Duck Pond Cellars in Oregon, had been granted that certification on select wines in its portfolio.

“Like in any category of wine, no matter the region or type we’re exploring, there is going to be good wine and not-so-good wine. That applies to the natural wine category as well,” explains sommelier Erica Archer. We chatted at a corner table at Maine and Loire, a natural wine bar and shop on Washington Avenue in Portland. She recommended we try a bottle of 2016 Terre de l’Élu called L’Aiglerie, a red “vin de France” made from old-vine cabernet blanc grapes. The winery, ironically, is located in the western France governmental department called Maine-et-Loire. Archer chose this one because she wanted me to experience the texture of it.

“Like in any category of wine, no matter the region or type we’re exploring, there is going to be good wine and not-so-good wine. That applies to the natural wine category as well,” explains sommelier Erica Archer. We chatted at a corner table at Maine and Loire, a natural wine bar and shop on Washington Avenue in Portland. She recommended we try a bottle of 2016 Terre de l’Élu called L’Aiglerie, a red “vin de France” made from old-vine cabernet blanc grapes. The winery, ironically, is located in the western France governmental department called Maine-et-Loire. Archer chose this one because she wanted me to experience the texture of it.

Archer is the founder of Wine Wise, a Portland-based company that offers wine tastings on sailboats in Casco Bay and guided regional wine trips. She also produces Portland Wine Week in mid-June. She does not specialize in natural wines, but she is very knowledgeable about them and introduces many to her customers.

In the tasting notes on the 2016 L’Aiglerie Archer created for Wine Wise’s wine club members, she describes it as “a medium-pink, slightly hazy color, with notes of ripe and wild dark cherry, blackberry, red currants, fresh mint, rich soil, graphite, and roasted bell pepper.” She also says the texture is “bone dry and medium-bodied, with medium-plus fine tannins and medium-plus acidity that lifts this wine with a vibrant freshness.”

I like it. A lot. Admittedly, though, I don’t really have a large frame of reference to compare.

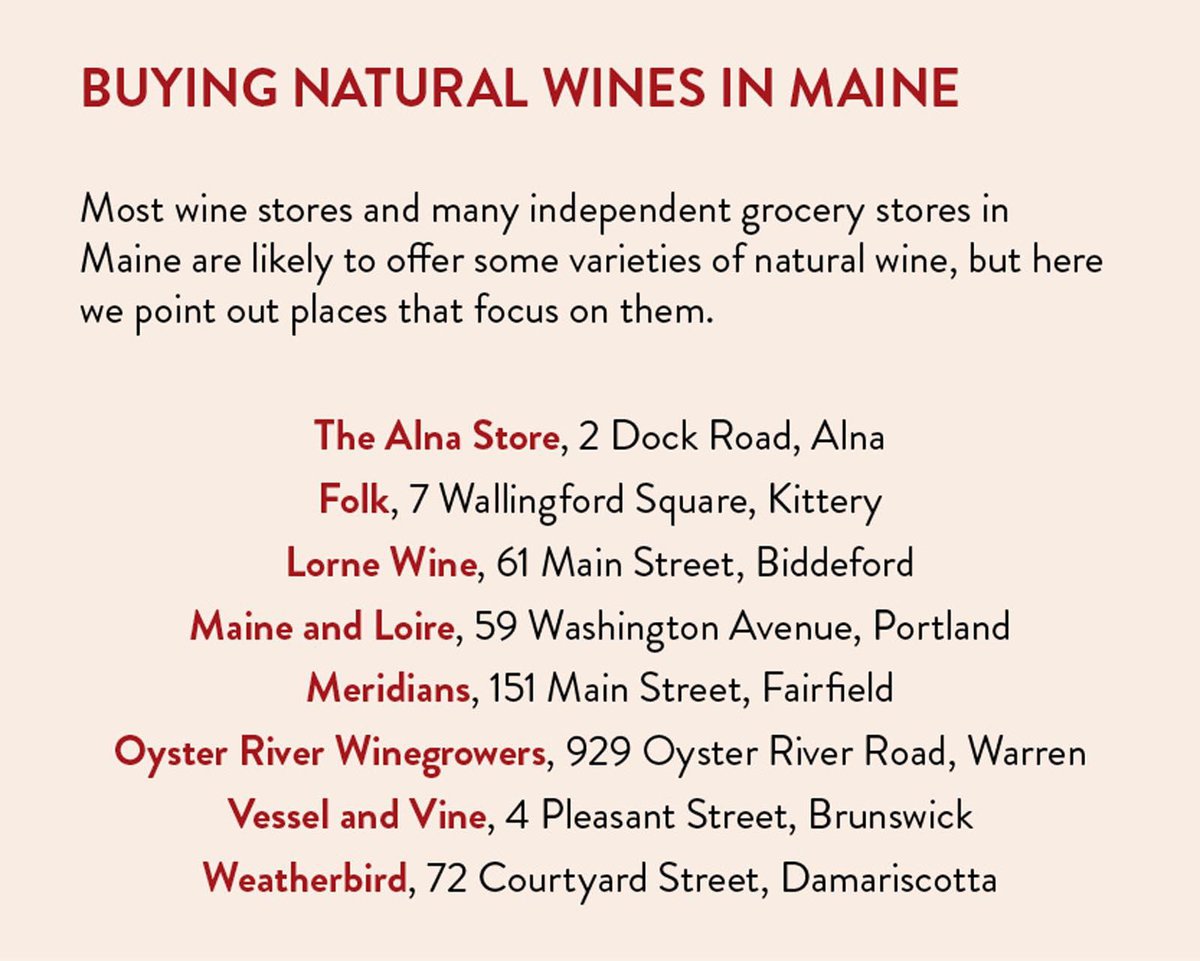

Archer says one of the best ways to understand what natural winemaking processes bring to the table is to work with a wine professional. They can help you make an apples-to-apples comparison, tasting a natural wine that you enjoy side by side with a conventional wine made from similar grapes grown in a similar region within a similar time frame. Archer stands at the ready to help you make such a match, but she’s also a team player and gave a long list of retail wine folks in Maine who could fit the bill. Should you care to have a wine drinking experience like Archer suggests, we’ve listed those here.

Archer says one of the best ways to understand what natural winemaking processes bring to the table is to work with a wine professional. They can help you make an apples-to-apples comparison, tasting a natural wine that you enjoy side by side with a conventional wine made from similar grapes grown in a similar region within a similar time frame. Archer stands at the ready to help you make such a match, but she’s also a team player and gave a long list of retail wine folks in Maine who could fit the bill. Should you care to have a wine drinking experience like Archer suggests, we’ve listed those here.

Cheers!