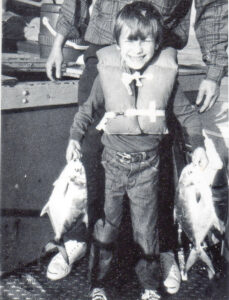

My evolution as a sport fisherman is a study in values transformation as my understanding of my relationship to fish, fishing, and Nature evolved over time.

I was a stone-cold killer the summer I was 14. I knew all the productive spots on a pond near our cabin in northern New Hampshire. One was under the dead white pine that stuck 50 feet out into the water; another was just a foot off the big rock where baitfish collected; and a third was above the underwater spring. I stalked largemouth and smallmouth bass from my 15-foot aluminum canoe, using a variety of lures. The jitterbug at midnight was particularly lethal.

Bringing home a stringer of fish was a matter of pride. My dad taught me to properly dispatch and clean them, after which we either froze the fish or ate them that day. This pattern continued until one day in mid-August when he looked into the freezer and realized the stock was too much to leisurely consume in the two-week period before our migration south. “You kill it, you eat it,” he said. “Don’t disrespect the fish.” I ate bass for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for two weeks straight, and then never again.

Bringing home a stringer of fish was a matter of pride. My dad taught me to properly dispatch and clean them, after which we either froze the fish or ate them that day. This pattern continued until one day in mid-August when he looked into the freezer and realized the stock was too much to leisurely consume in the two-week period before our migration south. “You kill it, you eat it,” he said. “Don’t disrespect the fish.” I ate bass for breakfast, lunch, and dinner for two weeks straight, and then never again.

That was a turning point in my approach to recreational fishing. It still courses through my veins, and I flyfish whenever and wherever I can. It’s a lasting bond between me and my dad, who died in 2008, and an equally strong one to Nature. Whether fishing for rainbow trout on a quiet pond or stalking giant redfish in the Louisiana marsh, I enjoy the chase. I don’t ice fish regularly. Working the tip-ups or fishing through a hole in the ice doesn’t hold the same allure for me as casting a fly.

Even if I don’t catch anything, I appreciate just being on the water. But since that bass-full summer long ago, I’ve released almost every fish I’ve caught. Recently, a commercial fisherman I know who used to sport fish called me out publicly, asking me if I’d ever “contemplated the horror” of practicing catch and release. Rarely is there an easy answer to any ethical stance. I know how to fight a fish quickly and release it largely unharmed so it can grow, spawn, die, and return nutrients to the ecosystem. I acknowledge fish feel pain, and that not every released fish ultimately survives. I try to minimize that pain by limiting the fight time and using barbless hooks.

There is often heated dialectic between those who fish for sport and those who fish commercially. Much of the conflict stems from matters of resource allocation: who gets how much access to a shared resource. Fishery managers get called out for giving too big an allocation to either side.

There is often heated dialectic between those who fish for sport and those who fish commercially. Much of the conflict stems from matters of resource allocation: who gets how much access to a shared resource. Fishery managers get called out for giving too big an allocation to either side.

I know several commercial fishermen who are avid sport fishers. I know people who were commercial fishermen and only fish recreationally now. I even know a few people who have stopped fishing altogether. The choice comes down to personal values, so naturally people have a broad range of opinions.

I understand those who argue that catch and release is unethical if you don’t plan to eat what you catch. My wife falls into this camp. I don’t begrudge those who sport fish and occasionally take a fish home. However, I do take issue when someone fills a freezer with uneaten fish or doesn’t respect laws pertaining to catch limits, gear type, and seasonality.

I ascribe to the same values as commercial fishermen who fish sustainably do. They abide by the laws and take care of the resource, operate within a community seafood system, and are transparent about their product and process. We all have a relationship to Nature. If we are aware of how our decisions can affect natural resources, we can stand behind those values.